On a pig farm in La Porte, Indiana, Belle Gunness killed two of her husbands, a handful of single men, and several of her own children before mysteriously disappearing in 1908.

To outsiders, Belle Gunness might have looked like a lonely widow who lived in the American Midwest during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But in reality, she was a serial killer who murdered at least 14 people. And some estimate that she may have killed as many as 40 victims.

To lure her last victim, Gunness wrote: “My heart beats in wild rapture for you, My Andrew, I love you. Come prepared to stay forever.”

He did. And shortly after he arrived, Gunness killed him and buried his dismembered body in her hog pen, alongside other corpses.

Although her farmhouse burned down in April 1908, seemingly with her inside, some believe that Gunness slipped away — perhaps to kill again.

The Origins Of The ‘Indiana Ogress’

No

Belle Gunness was born Brynhild Paulsdatter Storset on November 11, 1859, in Selbu, Norway. Little is known about her early life. But, for one reason or another, Gunness decided to emigrate from Selbu to Chicago in 1881.

There, Gunness met her first known victim: her husband, Mads Ditlev Anton Sorenson, whom she married in 1884.

Their life together seemed to be marked by tragedy. Gunness and Sorenson opened a candy store, but it soon burned down. They had four children together — but two allegedly died of acute colitis. (Eerily, the symptoms of this disease were quite similar to poisoning.)

And in 1900, their home burned down. But as was the case with the candy store, Gunness and Sorenson were able to pocket the insurance money.

Then, on July 30, 1900, tragedy struck again. Sorenson died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. Strangely, that date represented the last day of Sorenson’s life insurance policy as well as the first day of his new policy. His widow, Gunness, collected on both policies — $150,000 in today’s dollars — which she could have only done on that day.

But no one at the time chalked it up to anything but a tragic coincidence. Gunness claimed that Sorenson had come home with a headache, and she had given him quinine. The next thing she knew, her husband was dead.

Belle Gunness left Chicago with her daughters Myrtle and Lucy, along with a foster daughter named Jennie Olsen. Newly flush with cash, Gunness bought a 48-acre farm in La Porte, Indiana. There, she set about starting her new life.

Neighbors described the 200-pound Gunness as a “rugged” woman who was also incredibly strong. One man who helped her move in later claimed that he saw her lift a 300-pound piano all by herself. “Ay like music at home,” she supposedly said, by way of explanation.

And before long, the widowed Gunness was a widow no longer. In April 1902, she married Peter Gunness.

Strangely, tragedy seemed to return to Belle Gunness’ doorstep yet again. Peter’s infant daughter from a previous relationship died. Then, Peter also died. Apparently, he had fallen victim to a sausage grinder that fell on his head from a wobbly shelf. The coroner described the incident as “a little queer” but believed that it was an accident.

Gunness dried her tears and collected her husband’s life insurance policy.

Only one person seemed to be catching on to Gunness’ habits: her foster daughter Jennie Olsen. “My mama killed my papa,” Olsen allegedly told her schoolmates. “She hit him with a meat cleaver and he died. Don’t tell a soul.”

Soon afterward, Olsen vanished. Her foster mother initially claimed that she’d been sent to school in California. But years later, the girl’s body would be found in Gunness’ hog pen.

Belle Gunness Lures More Victims To Their Deaths

Maybe Belle Gunness needed money. Or maybe she had developed a taste for murder. Either way, the twice-widowed Gunness began posting personal ads in Norwegian-language newspapers to find a new companion. One read:

“Personal — comely widow who owns a large farm in one of the finest districts in La Porte County, Indiana, desires to make the acquaintance of a gentleman equally well provided, with view of joining fortunes. No replies by letter considered unless sender is willing to follow answer with personal visit. Triflers need not apply.”

According to Harold Schechter, a true-crime author who wrote Hell’s Princess: The Mystery of Belle Gunness, Butcher of Men, Gunness knew exactly how to lure her victims onto her farm.

“Like many psychopaths, she was very shrewd in identifying potential victims,” Schechter explained. “These were lonely Norwegian bachelors, many completely cut off from their families. [Gunness] beguiled them with promises of down-home Norwegian cooking and painted a very seductive portrait of the kind of life they’d enjoy.”

But the men who came to her farm would not have a life to enjoy for very long. They arrived with thousands of dollars — and then disappeared.

One lucky man named George Anderson survived the encounter. Anderson had come to the Gunness farm from Missouri with money and a hopeful heart. But he awoke one night to a terrifying sight — Gunness leaning over his bed as he slept. Anderson was so startled by the ravenous expression in Gunness’ eyes that he left immediately.

Meanwhile, neighbors noted that Gunness had begun to spend an unusual amount of time at her hog pen at night. She also seemed to spend a lot of money on wooden trunks — which witnesses said she could lift like “a box of marshmallows.” Meanwhile, men showed up one by one at her door — and then kept vanishing without a trace.

“Mrs. Gunness received men visitors all the time,” one of her farmhands later told the New York Tribune. “A different man came nearly every week to stay at the house. She introduced them as cousins from Kansas, South Dakota, Wisconsin, and from Chicago… She was always careful to make the children stay away from her ‘cousins.'”

In 1906, Belle Gunness connected with her final victim. Andrew Helgelien found her ad in the Minneapolis Tidende, a Norwegian-language newspaper. Before long, Gunness and Helgelien began exchanging romantic letters.

“We shall be so happy when you once get here,” Gunness purred in one letter. “My heart beats in wild rapture for you, My Andrew, I love you. Come prepared to stay forever.”

Helgelien, like other victims before him, decided to take a chance on love. He moved to La Porte, Indiana on January 3, 1908 to be with Belle Gunness. Then, he disappeared.

The Downfall Of Belle Gunness

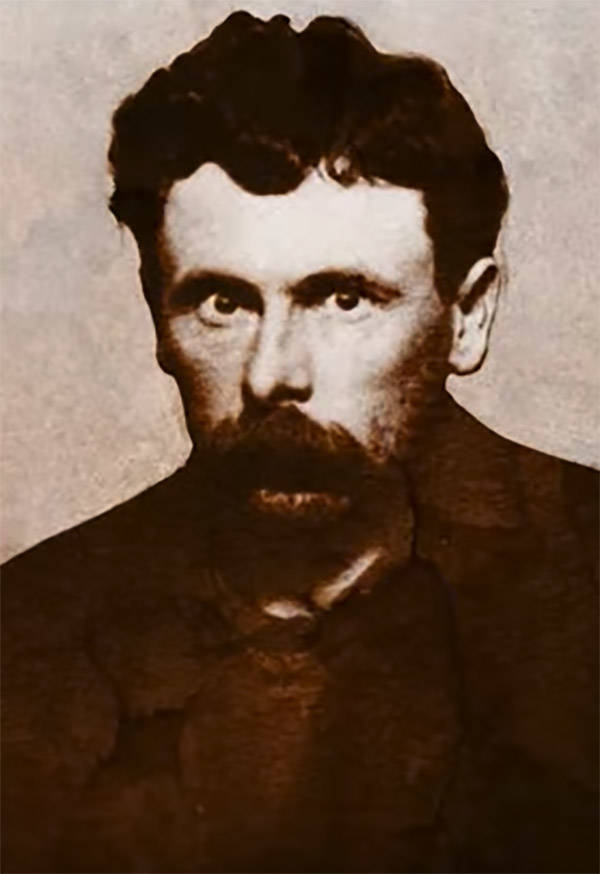

Ray Lamphere, the ex-handyman of Belle Gunness. Lamphere was later linked to the fire at Gunness’ farm.

So far, Belle Gunness had been able to largely escape detection or suspicion. But after Andrew Helgelien stopped answering letters, his brother Asle got worried — and demanded answers.

Gunness deflected. “You wish to know where your brother keeps himself,” Gunness wrote to Asle. “Well this is just what I would like to know but it almost seems impossible for me to give a definite answer.”

She suggested that maybe Andrew Helgelien had gone to Chicago — or perhaps back to Norway. But Asle Helgelien didn’t seem to be falling for it.

Concurrently, Gunness had begun to develop problems with a farmhand named Ray Lamphere. He had romantic feelings for Gunness and resented all the men that showed up at her property. The two once apparently had a relationship, but Lamphere had left in a jealous rage after Helgelien arrived.

On April 27, 1908, Belle Gunness went to see an attorney in La Porte. She told him that she had fired her jealous farmhand, Lamphere, which caused him to go mad. And Gunness also claimed that she needed to make a will — because Lamphere had apparently threatened her life.

“That man is out to get me,” Gunness told the attorney. “I fear one of these nights he will burn my house to the ground.”

Gunness left her attorney’s office. She then bought toys for her children and two gallons of kerosene. That night, someone set her farmhouse on fire.

Authorities found the bodies of Gunness’ three children in the charred rubble of the farmhouse basement. They also found the body of a headless woman who, at first, they assumed was Belle Gunness. Lamphere was quickly charged with murder and arson, and police began to search the farm grounds, hoping to find Gunness’ head.

Meanwhile, Asle Helgelien had read about the fire in the newspaper. He showed up in hopes of finding his brother. For a while, Helgelien assisted police as they sorted through the rubble. Although he almost left, Helgelien became convinced that he couldn’t do so without looking harder for Andrew.

“I was not satisfied,” Helgelien recalled, “and I went back to the cellar and asked [one of Gunness’ farmhands] whether he knew of any hole or dirt having been dug up there about the place in spring.”

In fact, the farmhand did. Belle Gunness had asked him to level dozens of soft depressions in the ground, which supposedly covered trash.

Hoping to find a clue related to his brother’s disappearance, Helgelien and the farmhand began to dig up a pile of soft dirt in the hog pen. To their horror, they ended up finding Andrew Helgelien’s head, hands, and feet, stuffed into an oozing gunny sack.

Further digging yielded more grisly discoveries. In the span of two days, investigators found a total of 11 burlap sacks, which contained “arms hacked from the shoulders down [and] masses of human bone wrapped in loose flesh that dripped like jelly.”

Authorities couldn’t identify all the bodies. But they could identify Jennie Olsen — Gunness’ foster daughter who had “left for California.” And it soon became clear that Gunness was behind some horrific crimes.

The Mystery Of Belle Gunness’ Death

Before long, news of the gruesome discovery spread throughout the nation. American newspapers labeled Belle Gunness the “Black Widow,” “Hell’s Belle,” the “Indiana Ogress,” and the “Mistress of the Castle of Death.”

Reporters described her home as a “horror farm” and a “death garden.” Curious onlookers flocked to La Porte, as it became a local — and national — attraction, to the point that vendors reportedly sold ice cream, popcorn, cake, and something called “Gunness Stew” to visitors.

Meanwhile, authorities struggled to determine whether the headless corpse they’d found in the burned farmhouse belonged to Gunness. Although the police found a set of teeth among the ruins, there was still some debate as to whether or not they belonged to Belle Gunness.

Curiously, the corpse itself seemed to be much too small to be hers. Even DNA tests that were done decades later — from envelopes that Gunness licked — were unable to definitively answer if she had died in the fire. In the end, Ray Lamphere was charged with arson — but not murder.

“I know nothing about the ‘house of crime,’ as they call it,” he said, when asked about Gunness’ murders. “Sure, I worked for Mrs. Gunness for a time, but I didn’t see her kill anybody, and I didn’t know she had killed anybody.”

But on his deathbed, Lamphere changed his tune. He admitted to a fellow inmate that he and Gunness had killed 42 men together. She would spike their coffee, bash their heads in, cut up their bodies, and put them in sacks, he explained. Then, “I did the planting.”

Lamphere ended up in prison because of his connection to Gunness — and the fire on her farm. But did Lamphere actually cause the fire? And did Gunness really die in the farmhouse disaster? Years after Gunness’ supposed demise, rumors surfaced that she may have faked her own death to escape potential capture. Or perhaps she simply wanted to be free to kill again.

Eerily, in 1931, a woman named Esther Carlson was arrested in Los Angeles for poisoning a Norwegian-American man and attempting to steal his money. She died of tuberculosis while awaiting trial. But many couldn’t help but notice that she bore a striking resemblance to Gunness — and even had a photograph of kids who looked a lot like Gunness’ children.It remains unconfirmed when — and where — Belle Gunness actually died.